Along Georgetown Road sits a farm with a storied history spanning more than 100 years.

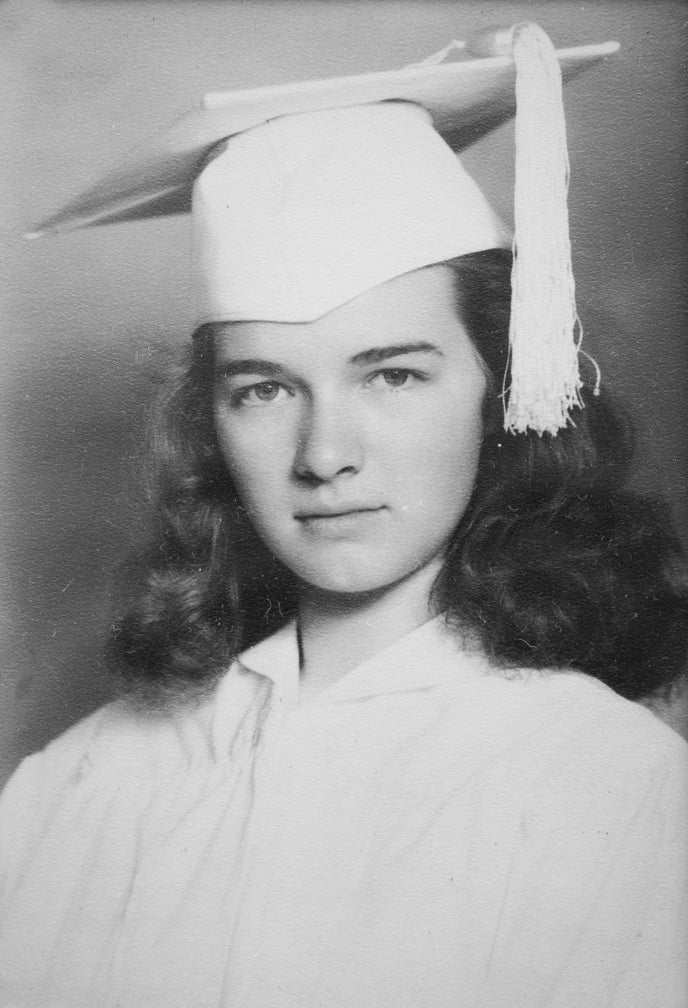

Woodlake Farm is the recent home of members of the Hockensmith family. Mary Anne Hockensmith, formerly known as Mary Anne Noel, became the head of her family’s farm, Woodlake, in August 1941. At the time, she was 17. She was the oldest of three and both her parents died before she turned 18. Her guardian was William Crouse.

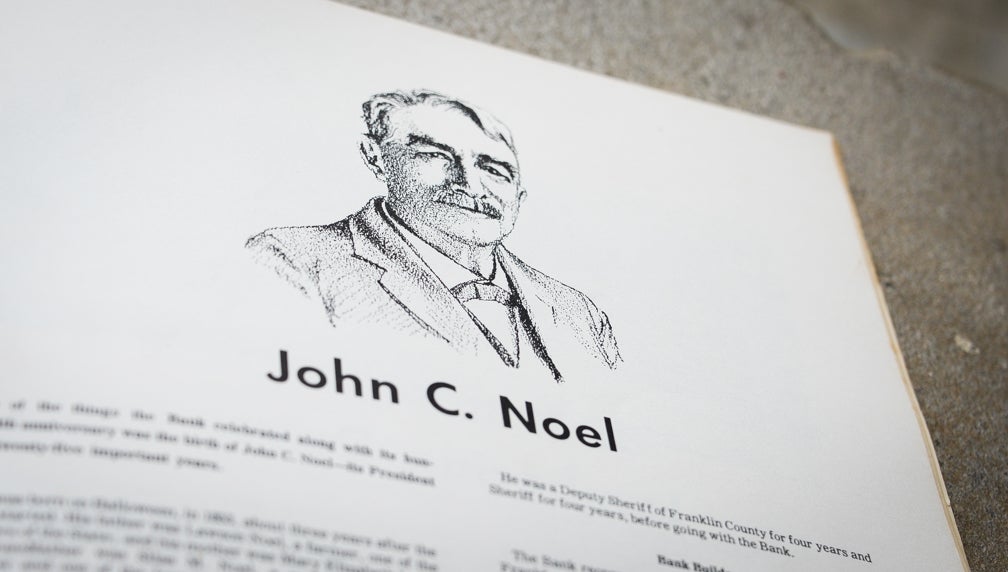

Mary Anne’s younger sister was Johness Noel and her brother was John Clay Noel III, the longtime banker at Whitaker Bank. Mary Anne’s father was John Clay Noel II, who was the president of State National Bank, and her mother was Agnes Crouse Noel. Mary Anne went to Good Shepherd School and graduated in 1942.

While others took care of the day to day work of the farm, Mary Anne still signed off on decisions while attending school at Saint Mary-of-the-Woods and then St. Mary’s of Notre Dame in Indiana where she studied nursing. Her siblings also attended college there. Mary Anne ended up returning to Frankfort in 1945 to be present on the farm.

Terry Hockensmith, one of Mary Anne’s daughters, said that her mother took the train from Frankfort to South Bend, Indiana, between home and school. At the time, the train was full of soldiers due to World War II. Mary Anne exchanged letters with various people throughout the country she met during her travels.

Crouse commissioned a man the family knew as Mr. Kitchen to work on the farm in Mary Anne’s absence. He also worked at other local farms. He left the farm and ultimately began working on King Ranch in Texas. Terry said that Mary Anne felt a “great responsibility” to come home.

The farm has a history before Mary Anne was born. The farm was originally owned by the family of suffragist Madeline McDowell Breckingridge. Her childhood at Woodlake is recalled in a biography about Breckingridge and describes how she rode all over the farm on horseback with her father and “romped” with other boys and girls in play.

“Those early years at Woodlake were years of joy and freedom,” the book said.

The main house on Woodlake was rebuilt in 1924 following a fire that burned the original house a few years prior.

Mary Anne married Freeman Hockensmith, another Franklin County native, in 1945. He died in 1984. They had 12 children who are now living locally or around the country. Terry said her parents met on a double date when Freeman was dating Mary Anne’s sister Johness, but those couples found that to not be a good fit, Terry said. Freeman served in World War II.

Mary Anne’s children still recall their upbringing on the farm. Her daughter Deborah said that she can remember working in the garden and stripping tobacco among some of her and her siblings’ chores. Terry said that the kids often rode horses and had friends over, too.

When asked if the family refers to the farm by its proper name, Woodlake, Terry said, “To us, it’s ‘home.’”

Deborah said that the kids had “contests” between them when milking cows to see who could squirt milk into the cats’ mouths from about 10 feet away. She said that because of her almost daily milking, she beat all the eighth-grade boys at school in armwrestling.

Terry said that her mother always offered visitors something to eat or a glass of iced tea. Stephen Hockensmith, a grandson of Mary Anne’s, said that she would often fix Sunday dinners for the family.

Family was an important aspect of live on Woodlake Farm. The farmhouse is the frequent gathering place for the Hockensmith Family for the holidays.

Wars fought around the world affected life at the farm. In World War II, war prisoners worked as farm hands while local men were out fighting the war, Terry said. Mary Anne’s son David Baker Hockensmith died in the Vietnam War around 1970.

Throughout her life, Mary Anne owned and bred horses for races. Most people who know her recall her love of horses. She began racing horses in the 1950s and continued to do so until 2013. Terry said that Mary Anne had horses compete on tracks like Churchill Downs, Keeneland, River Downs, Turfway and more tracks around the country. Mary Anne’s horses included Field Grown, Red Slugger, Pop n’ Fly, Willful, Series Seeker and War Romance. One of her horses, Clear Conscience won over $127,000 according to Equibase, a racehorse database. In 1979, Mary Anne won enough money to build a new horse barn, Deborah said.

Mary Anne’s horses won multiple stakes races, Terry said. She mostly raced and bred homebreds. Mary Anne sold a homebred yearling filly named Lucinda K, who produced Atswhatimtalknbout, a horse that came in fourth at the 2003 Kentucky Derby. Mary Anne has had 52 horses run in 570 races since 1976.

Terry said that Mary Anne visited the horse before each race.

“It was like seeing her grandchild,” Deborah said.

Deborah said that Mary Anne’s love of horses stemmed from her father. John Noel never learned to drive a car in his lifetime. He always drove a horse and buggy from Woodlake to the bank in downtown Frankfort. He also made the trip in the middle of the work day to eat lunch at home. Woodlake also had its own racetrack on the property during the days it was owned by the Burbridge family in the early in the 1800s.

“Mama always said that he didn’t want one that couldn’t go a two-minute mile,” Deborah said.

Deborah said that Mary Anne “was totally component and comfortable when taking those reins.”

The current upkeep of the farm falls to Stephen, Kevin Hockensmith and other Hockensmith family members. Todd Wylie helps out as needed. The farm is around 500 acres and is home to cows and various trees like Tulip Poplar and Northern Catalpa. The farm still is home to Woodlake with catfish, bass and bluegill. Kevin also maintains another farm in Versailles.

“It’s a lot of work. It keeps you busy,” said Stephen.

A place like Woodlake wants you take pride in it with your work, Stephen said. He’s lived in the area throughout his whole life, so he grew up working on a farm. He’s now the assistant roads superintendent.

Farm work teaches someone to be a steward of the land, Wylie said. The work is often from daylight to dark with little to no pay. Farmers see things grow and be destroyed.

“It makes you appreciate life,” Wylie said.