A habit that began partially out of necessity when dentist Will Renshaw was a college student has evolved into a second calling. And the products of that second calling can be found in Boston, Chattanooga, Tennessee, and, soon, in Michigan, too.

That second calling is a combination of his passion for music, a need to repair his own guitars and a bit of influence from his father and grandfather. Renshaw a dentist by day and, often, a luthier by night. That is, Renshaw makes handcrafted acoustic and electric guitars and some repair jobs, too.

“It’s really become this amazing passion for me, and I am lucky that people are actually interested in this and people want me to build them,” he said.

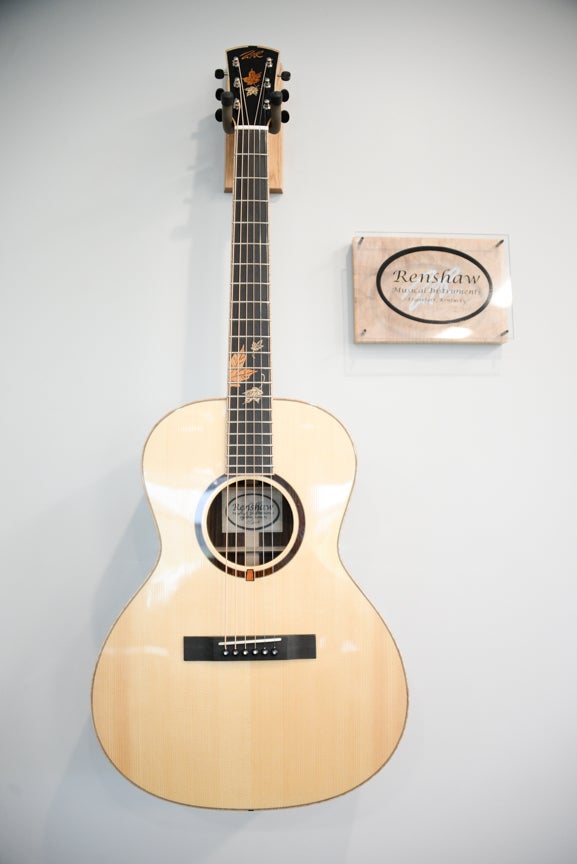

As Renshaw walked into his guitar workshop on a July afternoon, three finished guitars sat on stands in the center of the room, shining under fluorescent lights. On the walls were shelves of wood to be used in future musical creations, tools of the trade, sketchings of a guitar body and, in the back corner of the room, a framed image of Darth Vader. Next to the Darth Vader portrait is a broken acoustic guitar made by the company Fender once sold at a cheap price in the Sears, Roebuck and Co. Catalog. Renshaw eventually plans to restore it, but admits that the task will take a while.

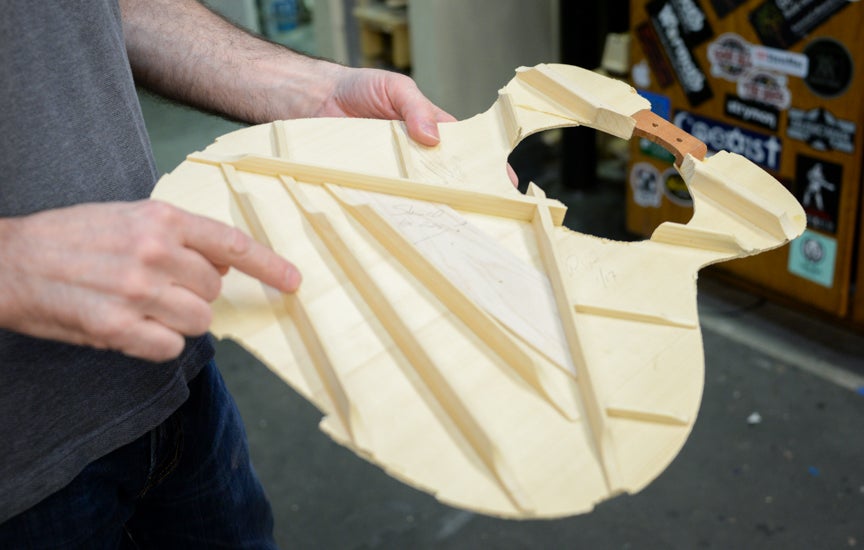

Renshaw also keeps around parts of guitars that didn’t quite make it, including the wooden side of a guitar that cracked in the drying process. He jokes that the broken or imperfect bits of guitars are his wall of shame, but he says the segments of the guitars also show that nobody is perfect. And, building instruments isn’t for the faint of heart.

“Every piece of wood is different. It bends differently. It sands differently. It shapes differently. And, for some reason, it will just split,” he said.

A number of the tools in Renshaw’s guitar workshop previously belonged to his father, and the drill press in his shop was once owned by Renshaw’s grandfather. As a child, Renshaw spent time in his father’s woodshop and developed skills that would come in handy as a college student.

Between playing gigs two or so times a week to pay for college expenses, Renshaw made his own guitar repairs — a practice that started in high school.

“I started repairing my own instruments because I couldn’t afford to get them repaired, and I figured that, if I screwed it up, I could take it to somebody,” Renshaw said.

Originally from Louisville, Renshaw received a bachelor’s degree from the University of Kentucky and played in the UK Jazz Band. He also attended UK for dental school.

In 1995, he came to Frankfort after being hired as an associate dentist at now-retired Gene Burch’s practice after doing an externship.

Then, about 10 years ago, Renshaw visited an exhibit at the Kentucky Historical Society in Frankfort about the commonwealth’s luthiers

“After talking to those guys and hanging out there for two weekends, I though ‘man, I can do that, and I’m kind of doing it already.’” Renshaw said.

He turned to one of the luthiers he met over the years — a Boston-based man named Sylvan Wells — and asked to spend time at the man’s guitar-making shop.

“Yes, but it will cost you” Renshaw recalled Wells saying.

For 10 hours per day over the course of a week, Renshaw worked as an apprentice.

Renshaw’s first self-made guitar was a bass. Then a friend told Renshaw, “I love that. I want you to make me two.” From there, the word spread organically mostly among people who have played one of Renshaw’s guitars. And, in the 10 years since he’s started making guitars for others, Renshaw has made more than 20, none of which are exactly alike.

“The combination of dentistry and guitar making, it’s really my love of intricate work,” he said. “I’m such a huge music fan and love playing so much that it was sort of a natural evolution, between playing in my dad’s woodshop, repairing my own instruments and playing then building.”

Renshaw takes pride in ensuring that each guitar he makes speaks to the interests and personality of the person for whom he’s making an instrument. In fact, that’s half of the fun of crafting guitars, he said.

“Anybody who wants a custom guitar has a story,” Renshaw said. “Each one of the guitars I make has a significance to that person.”

Another unique factor — While most guitars are made of one piece of wood, Renshaw makes necks of his guitars with multiple pieces, which adds strength.

The process of creating a guitar ranges from the shape, whether the person wants graphics on the fretboard and the shape of the instrument. Helping Renshaw during the guitar-creation process is the fact that being a dentist requires meticulous work in tight spaces. Still, he sweats a little each time he turns a stiff piece of wood into the curvy side of the guitar.

“It freaks me out every time because you heat it up to 400 degrees, steam it, force it around the mold and, if you’re lucky, it doesn’t crack,” Renshaw said.

One lengthy part of the process is applying and allowing the finish on the guitar to dry, which can take up to six weeks in some cases. And spraying finish is the only part of the process he doesn’t do in his home. For the last couple years, he’s traded with RS Guitarworks in Winchester. Renshaw does fine, inlay work on the company’s guitars and the RS Guitarworks handles the finish.

Depending on the pace at which he works — it’s more like a hobby than a second job — Renshaw says he puts 40 to 80 hours into every instrument. Some days, he may only do guitar-related work, including the occasional repair job, for 30 minutes. Others, if he has the house to himself on a weekend, he may spend eight hours working on guitars. A stress relieving activity, Renshaw says he can easily spend hours working on guitars without noticing the amount of time that’s passed.

Still, it’s possible that after weeks of work a guitar may not sound quite right once complete.

“Any real guitar-maker will tell you the same thing. They can put all of their heart and soul into the instruments. Some of them sound amazing. Most of them sound good, but every once in a while one doesn’t sound very good,” Renshaw said, noting that he’s been lucky so far.

In July, Renshaw was in the process of starting on a guitar for a customer in Michigan and had one additional order that had been partially paid for. From the first conversation to when the customer receives the instrument, it’s usually been six months.

Renshaw doesn’t plan on quitting dentistry any time soon, but plans to continue guitar-making indefinitely, into retirement. He likened guitar making to his former dental business partner Burch’s photography, a passion he chased after retirement.

“It is my retirement gig. I’m on the Gene Burch plan,” Renshaw said.

Asked about the comparison, Burch joked, “Well, we dentists have to do something that people like us for. People hardly say ‘I love that root canal you did.’”