By Charles H. Bogart

At the beginning of the 20th century, the quickest way to communicate with someone in another state was by the penny postcard.

In 1873, the first American picture postcard was printed by the Morgan Envelope Factory of Springfield, Massachusetts. The picture postcards had printed on one side of them views of various structures and exhibits of the ongoing Chicago Interstate Industrial Exposition.

That year also saw the U.S. Post Office (USPO) put on sale for a pre-stamped one cent Postal Card. Postcards were an inexpensive way to stay in touch with friends and neighbors who had moved away from each other. The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago was a turning point in the use of picture postcards. Everyone who went to the Columbian Exposition sent postcards home to family and friends to show that they had been to Chicago.

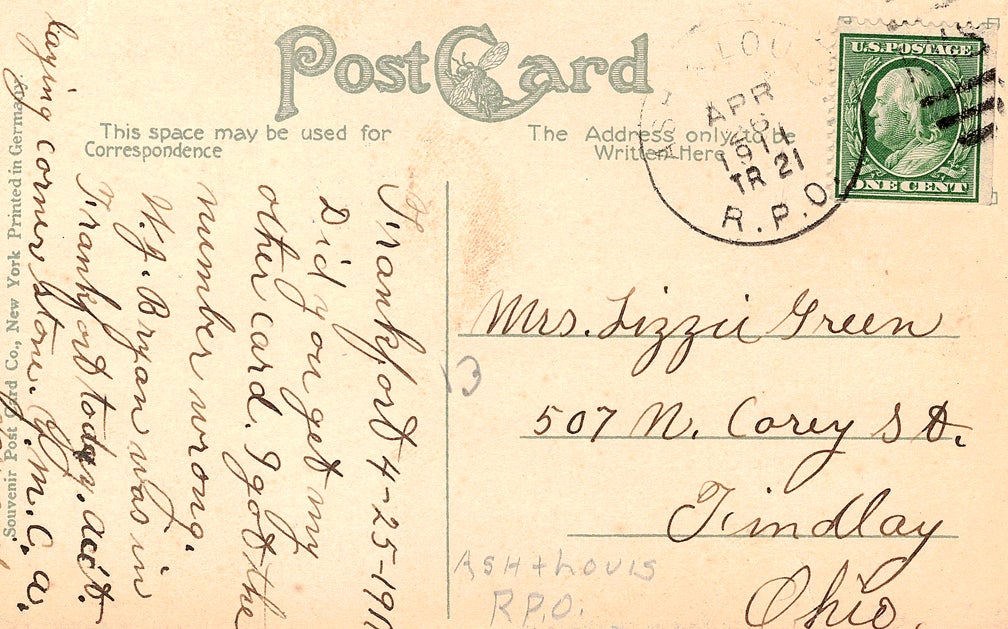

Picture postcards, at the time, did not have a divided back. The back of the card could only be used for writing the recipient’s address. All correspondence had to be on the front of the postcard.

On March 1, 1907, the USPO issued new rules governing picture postcards. The post office allowed private citizens to write on the address side of the postcard. It was on this date that picture postcards were allowed to have a divided back. The picture postcards were divided into two equal parts: the right side for the address and the left side for the message.

A caveat about colored picture postcards: There was no color film available before 1946 for use in making picture postcards. The photo used to create the full color picture postcards was shot in black and white. The photographer noted on the black and white image the color of the various items in the photo and sent the photo and description to Germany. In Germany, artists colored the postcard in what they assumed were the correct colors based on the photographer’s description. Thus, any correlation between the actual color of an object and what the artist imagined it to be is purely coincidental.

By 1910, every city and town in the United States felt it imperative to have for sale one or more picture postcards of a building or scene highlighting their town’s desirability as a place to live. Frankfort was no exception to this rule, and numerous local view postcards were offered for sale at various establishments. One of the picture postcards for sale in Frankfort was of the Singing Bridge.

During the first half of the 20th century, USPO provided overnight mail service between many cities that were less than 500 miles apart — New York to Chicago as an example. This was accomplished thanks to the Railway Postal Service (RPO) and twice daily home delivery of mail.

In 1864, RPO cars were added to passenger trains. The RPO car was normally located behind the locomotive, however, depending on the volume of mail handled, the RPO car could either be a complete car or half of a baggage car. The RPO car was staffed by two to 10 workers. The car’s purpose was threefold: to sort the mail it received from post offices along its route, to deliver mail to post offices along its route and to forward mail to post offices beyond its route.

Mail was picked up and dropped by the RPO car either from a baggage cart at a depot or on the fly. In Frankfort, mail was loaded and unloaded from the RPO car at the Broadway Depot during the unloading and loading of passengers. However, in Bagdad it was done on the fly. In Bagdad, the mail pouch was thrown off the train at the depot by an RPO clerk, while the RPO mailbag retriever snatched the local mailbag from its stand without the train stopping.

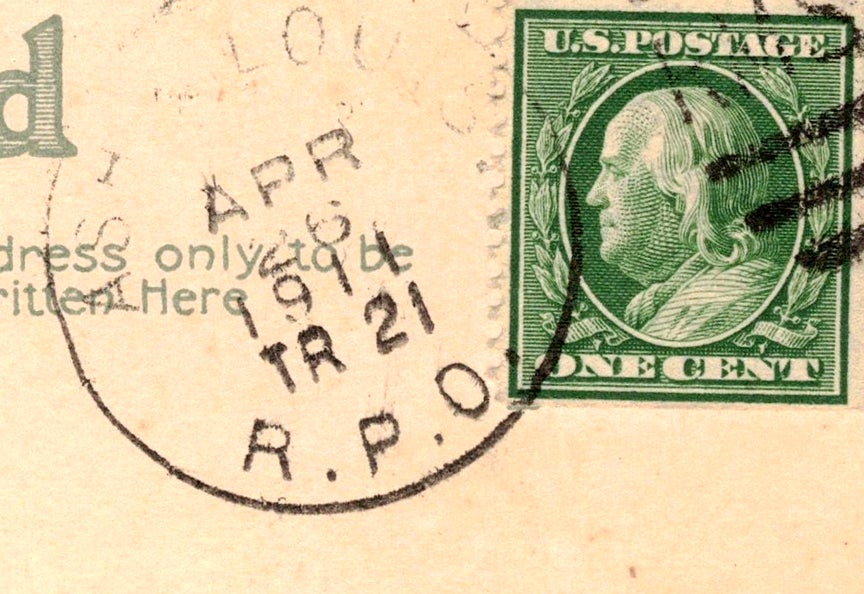

The Chesapeake & Ohio Railway (C&O) carried an RPO car from Ashland to Louisville and back to Ashland each day. This train ran daily through Frankfort as Train No. 21 westbound and as Train No. 24 ran eastbound. Now, each RPO car, just like each post office, had its own cancellation stamp. The cancellation stamp carried onboard the two C&O Trains read as follows: “Ash-Lou RPO, date, TR No 21” or “Ash-Lou RPO, date, TR No 24.” Train No 21 departed Frankfort at 9:04 a.m. for Louisville while Train No 24 left Frankfort at 7:42 p.m. for Ashland.

One postcard of the Singing Bridge was mailed April 26, 1914, and canceled onboard C&O Train No. 21. Its trip to Findlay, Ohio, can be recreated as follows: “Mrs. Melroy” walked the postcard to the depot and handed it up to Train No. 21’s RPO mail clerk just before the train pulled. The postcard was canceled on board the train and placed in a a mail pouch destined for Cincinnati, Ohio.

At 10:45 a.m., as the RPO car passed the Anchorage, Kentucky,depot, the mail pouch was tossed off the train. At Anchorage, the local mail was removed and the mail pouch containing the postcard was strung up to be caught at 1:40 p.m. by Louisville & Nashville Railroad (L&N) Train No 6, which delivered the mail pouch with the postcard to Cincinnati at 4:35 p.m. In Cincinnati, the mail was sorted at the RPO Post Office and the postcard was placed in a mail pouch bound for Carey, Ohio.

The mail pouch was placed on New York Central System (NYC) Train No. 2 that left Cincinnati at 9:02 p.m. for Sandusky, Ohio. The mail pouch was unloaded from NYC Train No. 2 RPO car at 3:15 a.m. at the Carey Depot. At Carey, the mail was quickly sorted and the postcard was placed in a pouch destined for Findlay via NYC Train No. 121. This train left Carey at 8:10 a.m. and arrived at Findlay at 8:40 a.m. just in time to make the start of the morning mail delivery.

The Capital City Museum is looking for other RPO mail to or from Frankfort.